How a Bathurst winner helped me nail turn five at The Bend

COACHES are a key component in most sports, leading their teams of men or women to success or falling on their sword when failure awaits. Their role in motorsport is growing, too, with professional drivers searching far and wide for expert advice that can help them hone their own craft behind the wheel.

WORDS: Richard Craill IMAGES: Porsche Cars Australia

It makes sense, of course. Why should motorsport be any different to any other professional level of sporting achievement, where coaches guide, inform, motivate and, if required, discipline athletes in a bid to help them achieve their maximum?

The fabled Rob Wilson in the UK is one example. Paul Morris has forged a stout reputation more locally doing exactly the same thing. British ace James Winslow still races and coaches a mix of young stars and amateur talent. The list is long and it continues to grow ever longer as drivers who no longer race professionally turn their attention to teaching others how to do it better.

But does it really work? What if you’re a complete novice? Or perhaps, and somewhat more dangerously, what if you know a lot about the mechanics of driving but rarely have the opportunity to get it together on a circuit? How influential can a coach be when you need to find seconds – and not the hundredths of seconds that a professional driver needs.

We went to find out and found the truth of the matter in one single corner at the epic The Bend Motorsport Park, an hour outside of Adelaide in South Australia.

**

ONE DAY in the distant future, when many more races have been won and lost, it’s not hard to imagine turn five at The Bend becoming one of those iconic corners; the kind spoken of with reverence and awe as many do when they reference names like ‘Hay Shed’ or ‘McPhillamy’.

In designing the circuit, it was, in fact, the high speed, ragged edge sweeper at Phillip Island on which turn five at The Bend was based. Though running in the opposite direction, it is a corner that in some race cars and in good conditions can be taken without lifting one’s right foot from the throttle. In other cars and in other conditions, it’s one of those nearly corners. As in, nearly flat, or nearly in the wall.

As the circuit rises out of turn three, a challenging left hand corner with a late and long exit, The Bend sweeps uphill and to the right through four which in just about anything is an easy flat sweeper.

Then emerges turn five, sweeping to the left with an apex that is somewhere on the far side of the inside kerb.

On the outside is grass. On the inside is a concrete wall that you’ll meet firmly if you run wide. This is not a corner that you want to tempt with wild, lurid oversteer on exit or a push onto the grass.

Already in it’s infancy it has claimed names: John Bowe, yes that John Bowe of two Bathurst 1000 victories, of 12-Hour success and of the 1995 Australian Touring Car Championship, was it’s first ever victim – his Ferrari did not enjoy a trip wide on the exit of this fearsome sweeper and ended parked firmly and quickly into the inside concrete that awaits such an error.

So if it can claim one of the best Touring Car drivers of a generation, driving a car loaded with sticky Pirelli’s and more downforce than most racing cars, how can an amateur driving a properly fast road car be expected to negotiate it safely?

Such was our mission during the launch of the eighth-generation Porsche 911, held recently at the circuit on a bright, warm sunny day in late March.

This was more than just a junket allowing a bunch of privileged motoring journalists a chance to hack about in the latest-gen 911 on someone else’s dime. The drive program at The Bend was geared towards education; a guided process of negotiating the circuit in an effort to get the most out of a limited number of laps.

In true Porsche fashion, the philosophy was clear: getting the most out of the track would allow you to get the most out of the car which was the most important thing after all.

The day started with a guided lap of the track, in this case the 3.4km West circuit.

The choice of circuit was smart; the longer International circuit used by the Supercars last year includes five corners with average speeds somewhere above the 180km/hr mark, that would have created just a little too much trepidation among Porsche and their limited number of 992s in the country at the time.

The West Circuit, instead, offers a similar driving challenge without quite so much peril; but retains the technical challenge of the full circuit.

The guided lap saw the group taken to key positions on the circuit for an active demonstration on how to manage it during our driving experience. We’d watch, the instructors – in this case noted racers Karl Reindler, Luke Youlden, Dean Canto and Garnett Patterson – would teach.

As Reindler described the phases of the corner, from braking to middle to entry, Patterson hustled the bright red 992 hero car through the corner; first at slow speed to allow us to see the lines and then at ‘about 90%’ to see what it was like at speed.

As a rare opportunity to stand that close to a car going that quickly, it was a startingly effective way to pick up on how the car was behaving, what parts of the circuit to use and what not to do.

This carried on: the focus at turn six was braking and how to carry the middle peddle a long way into what was the slowest point on the lap. At turn nine (14 on the international circuit) it was about driving to memory – recognising that the exit point was way beyond the line of sight and that you had to commit to the fact it was there and that getting it wrong compromised the next two corners and most of your lap.

Which then brought us to the point of actually getting behind the wheel and sampling it for ourselves; led around in groups of two with an instructor in front driving a previous-generation GT3.

THE VALUE of input from professionals came immediately after my first, 15-minute run.

I was frustrated. Frustrated both with my own inability to articulate everything I already knew and the other aspects we’d been taught to that point. I was so far behind both the car and the circuit that I’d missed apexes, braking points and exists ad nauseam while trying to hang on to it all.

As we waited to swap cars for a second run, Reindler wandered over for a chat as I expressed my frustration of being so far behind where I knew – or perhaps, expected – I could be.

“Now you’ve done it, you know what to expect so it’ll be easier. Make sure you keep your eyes up.. remember you’re looking to where you want the car to go.. and don’t forget to relax. If you’re uptight, the car will feel that way too but if you relax your inputs will be smoother and it will all string together better.”

Of course it sounds simple – but it was exactly what I needed to hear and the second session was much smoother, much quicker and as a result, much more enjoyable.

**

THE VOICE of Bathurst winner Luke Youlden, who when not winning Australia’s most famous race doubles as the deputy boss at Porsche’s Sport Driving School in Queensland, crackled over the two-way radio that linked his leading GT3 with the pair of 992 press cars behind.

It was on the cool down lap on the third of four runs during the day and while things were coming together I knew I was struggling through turn five – missing the apex and not only slowing my corner exit dramatically, but risking that wild moment in the undergrowth on the exit, too.

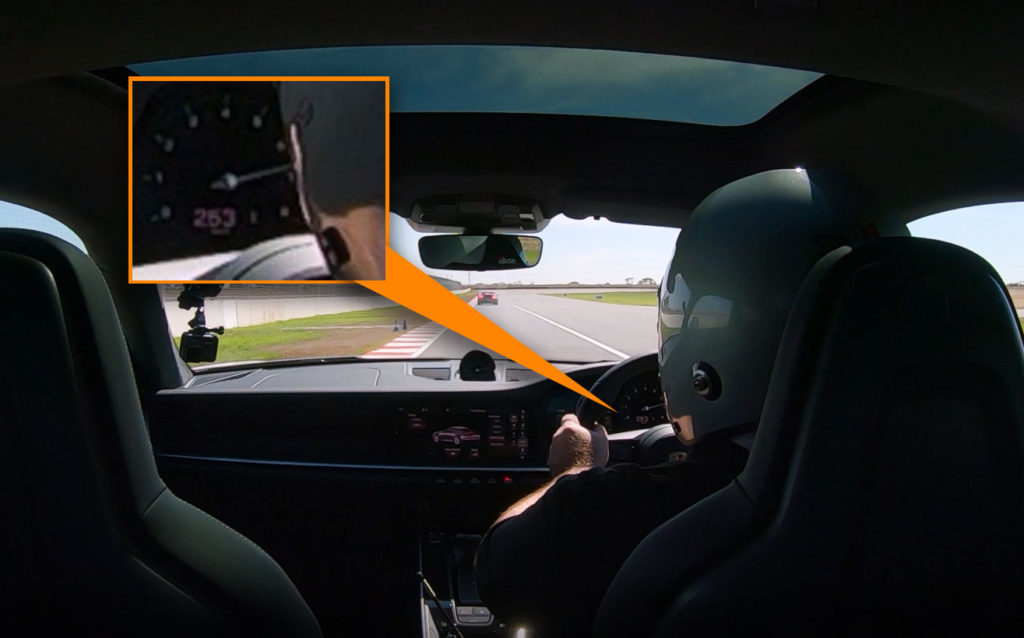

In the 992 we touched 185km/hr before the point, marked on the circuit by cones, where to either lift or in my case have a ‘confidence brake’ before turning the car into the quick left hand sweeper.

Of course, because proper racing drivers operate on a slightly different wave length to the rest of us, Youlden was way ahead of me already.

“Craillsy, I’d like to see you get to the apex a bit sooner here at five,” he said over the radio as we passed through the corner itself while cruising back to the pits.

“As we said on the track walk, because you’re travelling quite fast at that point even being a meter late turning the car in makes a huge difference to where you end up positioning the car.

“Get it in a bit earlier and you’ll carry more mid-corner speed and the car will be more stable through the corner and you won’t risk dropping off on the exit so much.”

It was, of course, superb advice. It pinpointed exactly what I was doing wrong and offered the solution. Great coaching – though how he had the ability to see via the rear-vision mirror in a GT3 that I was wide of the mark in the middle of a 165km/hr corner I don’t know.

“In a road car with a road tyre, especially on a circuit with as low grip as this, you find yourself turning at a different path to the trajectory of the cars,” Youlden continued.

“..so you’re actually aiming for the grass but it will put you on the (apex) kerb. Bare that in mind for the next sessions that at the speed you’re traveling the car is sliding at six or seven degrees difference to the tyre.”

As we neared the pits, the GoPro rigged in each car recorded me saying “That’s F*&king good advice,” to no one in particular.

And it was.

On the final run, with everything learned throughout the day, I turned in earlier at turn five, hit the apex perfectly – if I do say so – and the world was different. I was on the throttle earlier, the car was more stable and all of a sudden there was more road to my right where before I would warily watch the side in fear of firing it off in a bout of understeer or ability failure.

It was far from perfect, of course, but with even just a few hours of expert guidance and input from professional drivers and thoroughly excellent blokes I could feel my own progress; to the point that by the end of the final session I was starting to feel the car as well.

There were no lap times recorded on this day so there’s no measurable way to judge the improvement I found with their help.

The immeasurable stuff, though, like confidence, attitude and approach, were all significantly better in the last session than the first and that must mean something. And it certainly felt much quicker.

By the end of the day I could stay with Youlden’s leading car with much less effort and even though he was driving to a pace, that was something.

Driver coaching is a growing part of motorsport and an increasingly important one at that.

While finding hundredths of a second for a hotshot Supercars ace may be good business, it’s cases like mine that will be perhaps the most significant contributions they will make to the sport as their role as coaches evolves and grows.

There is, of course, only so much they can do with the talent (or lack thereof in my case) they are given.

Yet if they can transform the driving of a fat bloke with fists of ham and a brain of jelly in the space of ninety minutes, imagine what they can do for someone who actually has some ability.

Thanks to Porsche Cars Australia for their assistance in making this story possible.