The Case for Lang Lang

Since the 1950s, the Lang Lang Proving Grounds have been the mysterious test track for all things General Motors, and now, in a post-Holden era, the venue presents a wonderland of automotive opportunities.

When the pin was pulled from GM Downunder at the start of 2020, the fire sale of company assets saw some prize jewels up for grabs.

Enter VinFast, a rapidly expanding Vietnamese-owned automotive brand, which made a swift move into the Australian market, picking up ex-Holden, Ford and Toyota engineers for their Port Melbourne office.

Concurrently, the company invested $36.3 million into securing the Lang Lang facility.

However, when the local engineering efforts were shuttered after a year, thanks to the pandemic, the Proving Grounds found itself on the market once again in August 2021.

Interestingly, as of now, the property is seemingly off the market, adding an intriguing twist to the ongoing tale.

Here is the story of Lang Lang and its prospects to one day become the centrepiece of our automotive world again.

Genuinely Massive

If you don’t know where Lang Lang is, there is a very good chance you’ve driven straight past it en route to Phillip Island.

Hidden behind thick scrub on the Bass Highway, 10km past the Shell service station that marks the turnoff for the Lang Lang township, the Proving Ground is a sprawling block covering some 877 hectares.

To give this some perspective, the entire plot of the Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit is 256 hectares, the Albert Park precinct is 225 hectares, and Sandown is 112 hectares.

Lang Lang is large, and it was essentially formed out of frustration.

In refining the early Holdens, engineers battled the variables and changes in public roads around Melbourne, from the Hume to the Dandenongs, with baseline testing a practical impossibility.

What was required was a control set of every driving condition imaginable, and armed with knowledge earned from GM’s immense proving grounds at Milford in Michigan, plus Phoenix, Arizona, and Manitou Springs, Colorado, the blueprint was set.

However, there were challenges from the outset.

Four adjoining blocks were purchased to build the required infrastructure, although two different road alignments split them, plus they were located in two separate shires.

Ultimately, Holden acquired 1,000 acres of Crown Land for £8,000 in 1955, or $308,000 today, with the first stage of construction noted as having a £200,000 cost ($7,715,000 today), including all land purchases.

Once combined, GM had hugely contrasting terrain at its disposal, from flat land at the front of the facility to hills in the rear, covered with typical Aussie scrub through to rainforest.

In its prime, the venue witnessed millions of kilometres of vehicle assessments every year, with an army of test pilots working three shifts around the clock to iron out the kinks in pre-production specials, dating back to the FC model, which began tuning in 1957.

It was more than just Holden, too, with GM sending vehicles from around the world put through the wringer.

One of the first jobs was to erect 18km of eight-foot-high perimeter fencing, which remains cloaked in black mesh to this day in an effort to keep prying eyes away, with daily patrols formally employed to check that no telephoto lens-wielding trespassers entered the facility.

Skippy keeps a watching brief over activities…

Enter the Speed Loop

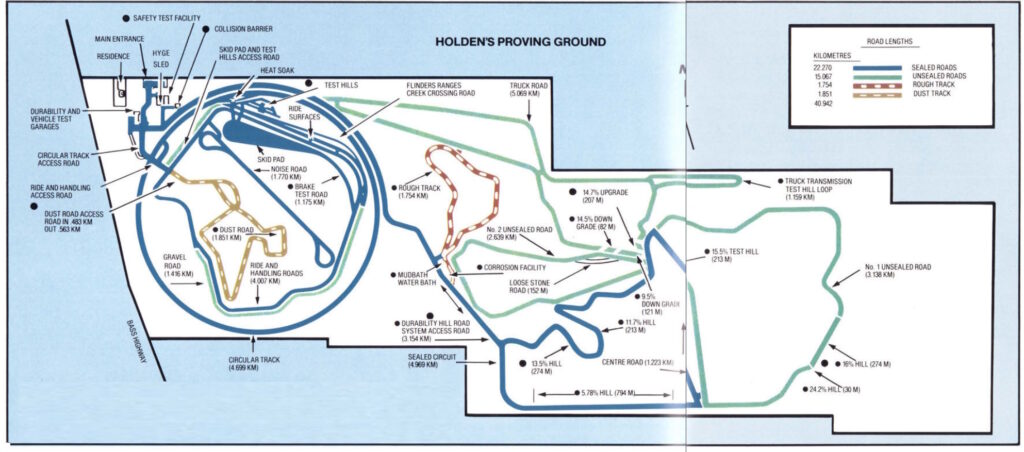

With a network of 44km of roads, with approximately half sealed, the all-encompassing battery of tests that remain available is staggering.

Perhaps the most striking feature at Lang Lang is the 4.7km long ‘Speed Loop’ or circular track, which is unlike anything you are likely to have ever seen.

Four lanes wide and progressively banked, the gentle curve is smooth under wheel – from the top lane at 180km/h, you don’t require any steering input at all, with centrifugal force keeping you straight and off the Armco.

Neutral steering is also available on the lower lanes at 120km/h, 80km/h and 60km/h.

Constructed at a cost of £300,000, or $10,500,000 in today’s money, the Loop allowed for sustained speeds of up to 250km/h, although tales of when it goes wrong at that speed, including for a testing race car, are legendary.

The surface itself is fresh – in modern times, the blacktop was most recently refinished in 2018, when 7,500 tonnes of asphalt was laid at a cost of $7.2 million.

A tall wire fence now tops the Loop, installed after a kangaroo apparently smashed through a car windscreen at a massive speed, however, to this day, the infield is still crawling with wildlife, which keeps drivers on their toes.

Could you imagine a NASCAR race there?

Probably not – at 2.915 miles, it would dwarf even Talladega, and the lack of distinct corners would most likely result in a procession.

On the infield of the Loop is a range of different features, including a large ride and handling road network covering every possible scenario, a massive skid pan area, complete with a significant runup, ideal for testing brakes or acceleration, a noise road, a 4WD park and dust road network, four test hills of varying gradients, from 15 up to 30 per cent, plus more.

Then there are low coefficient of friction surfaces to simulate driving on ice, and even tram tracks, a unique Melbourne-inspired test feature.

The Canberra Times, 16th September 1984

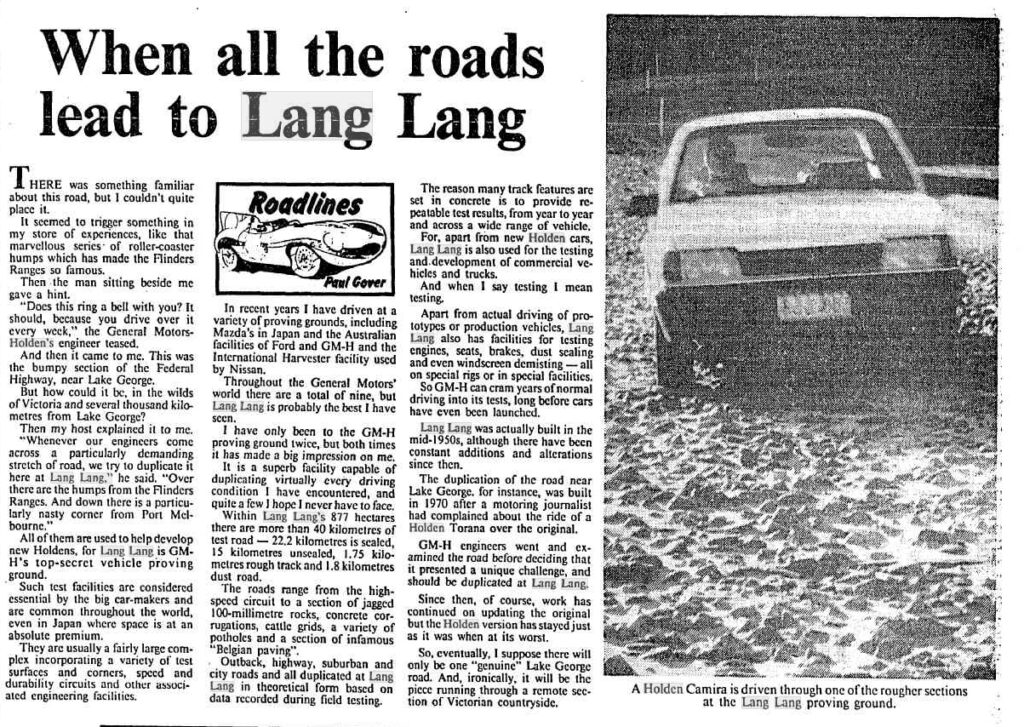

One of the main attractions outside of the Speed Loop are the durability roads, which were purpose-built replications of the worst things you could ever drive over, including deliberately concreted potholes, jagged rocks, corrugations, cattle grids, Belgian Pavement, water and mud baths plus more, with the permanent fixtures ensuring consistent results.

We were told that 3,650 laps of the main test loop would simulate the lifetime of a car – if a machine could survive that, Holden would gladly slap a warranty on it.

After one lap, I was about ready for a lie-down and a dentist visit.

Further afield is a quarry, which provides a spectacular backdrop, with vistas from the top of the hill flowing down into Western Port Bay and French Island.

Outside of the main driving activities, a wide array of automotive science can be carried out at Lang Lang.

From emissions testing facilities, which were updated in 2018 at a cost of $8.7 million, to heat soak sheds and cold rooms covering a temperature range of -40 to +50 °C, crash test facilities, and corrosion testing, the venue caters to everything you could think of.

Backing it all up, an impressive workshop allowed for ongoing inspections and on-the-fly modifications, with the buildings covering a combined 11,920 square metres.

A thorough rundown of the facilities would require a book over a mere TRT feature.

Now and The Future

A little while ago, I wrote about the time I visited the Aldenhoven Testing Centre in Germany.

It was sleek, efficient, and oh-so Germanic, but it thoroughly lacked the grand scale of Lang Langs.

While some portions are showing signs of age, the outfield around the road network remains neatly presented, although you would imagine that upkeep of that magnitude would be considerable.

These days, users outside of General Motors or Vinfast can utilize the venue, and car clubs have had special visits scheduled in recent times, too.

Security, however, is still tight, although not to the level of putting tape over your smartphone camera lens, a practice of days past.

Around the various tracks these days, you can find a mixture of users undertaking various tasks, from testing and tuning to validating new technology, plus media shoots and out-and-out road testing, such as above.

Unthinkable a few years ago, Mitsubishi used the facility to fine-tune the 2024 Triton ute, utilising the very facilities that bred generations of GM’s finest.

Upon meeting the staff, one thing that grabs you is that how fiercely proud they are of their facility.

While the significant signage around the venue has been Vinfasted, Holden coffee mugs abound and are sipped on as excellent stories of the past life for the proving grounds are retold.

The 24-hour-a-day operation of the past is now a memory, but hopefully, it will be documented one day.

Another thing that grabs you is that this is one of the last untouched natural environments in the area, which has been a hot topic in recent years when the property has been on the market, with the State Government implored for a time to purchase the block.

Locals aren’t keen on another sand mine being established in the area.

Outside of the kangaroos, wallabies and echidnas that freely graze the grounds, attendees are constantly warned of the ever-present danger of snakes, which I entirely believe after being chased out of the nearby Gurdies on my mountain bike by multiple red belly blacks…

Here’s hoping that whatever the next life for Lang Lang is, it contains a motoring flavour.

An asset this good shouldn’t be lost for an industry in need of places to go fast.

With Sandown on the way out and Geelong a pipedream, opening Lang Lang up for expanded public consumption would be a massive win for the motoring-minded public.

When you look at the business models of modern racetracks, a vast majority of their trade is garnered from outside competition meets, and that said, the very basis of some epic racetracks are waiting to be forged through the Lang Lang hills or Speed Loop infield.

Then, when you consider that The Bend came in with a price tag of over $100 million, and their new drag strip alone cost more than $30 million, at less than $40 million, Lang Lang was a veritable bargain for Vinfast.

Fingers crossed, someone with that sort of spare change can keep this magical place alive.