The Battle of Bathurst: Lawyers Engaged

In the first leg of our multi-part feature on the Battle of Bathurst: V8 Supercars versus Super Touring, we delved into the background of the motorsport civil war, the founding of AVESCO, early political plays, and the ultimate outfoxing that saw a second Bathurst 1000 be permitted in 1997.

Read: Part 1 – The Battle of Bathurst: V8s Vs Super Touring, TV Wars & Council Plays

Read: Part 3 – The Battle of Bathurst: Taking a Financial Bath, Two Bathurst 1000s in One Month

Read: Part 4 – The Battle of Bathurst: Publicly Disappointed, Epic Race & the Blame Game

Read: Part 5 – The Battle of Bathurst: Death Threats & Regrets, Epilogue to Motorsport’s Civil War

Here in part two, we unpack the incredible power struggle as it played out in the media of the day, featuring a raft of sub-plots that dominated headlines through a tumultuous season of motorsport.

Lock it in: Two-Litre versus Five

By the end of January 1997, Super Touring was locked in with a long-term contract to the traditional October long weekend Bathurst event.

Promised was a field comprised of 10-15 internationals set to be joined by 20-25 local entries, plus 20 GT Production cars, with plans to bring entrants from Italy, Germany, the UK, Asia, South Africa and the USA.

The stage was set for a crown jewel event in the Super Touring world.

Date clashes, though, were raised early, with the event going up against the German series finale, while it was also noted that the British contingent would have to be back on track a fortnight after Bathurst in the UK for the Donington TT.

Another issue was that almost all of the factory budgets for the year had already been set in stone, and then there was developing ostensibly sprint race vehicles for long-distance use – the Germans were adept at this for racing on the Nürburgring, others less so.

Some from the V8 side threw barbs around the expectation for the Two-Litre cars not going the distance at Bathurst.

It quickly became apparent that technical and driver support for the local BMW, Audi and Volvo teams was seen as a logical solution to provide a high-quality field for those factory outfits, saving them from having to transplant their entire European operations.

Subsequent to the announcement, PROCAR, the custodians of the GT-P Championship, noted that they would not tolerate being the poor cousins of Super Tourers following the invitation for their cars to enter the race, although Mazda was keen to bring the RX-7SP out of mothballs for the occasion if possible.

Big talk postulated that the best of the production breed could take it to Super Touring over a race distance.

AMP would continue as the event’s sponsor. One month before the 1996 race, the financial services company claimed naming rights for that year’s Five-Litre meet, replacing Tooheys in a one-plus-two deal that was subsequently taken up.

Channel 7, meanwhile, was swiftly on the front foot and quickly circulated legal warnings, threatening to sue publications that confused the one and only Bathurst 1000/The Great Race with the Australian 1000 Classic.

In the press, BTCC boss Alan Gow did not go backwards in coming forwards when Super Touring was confirmed for Bathurst, conveying to Auto Action:

“It may hurt that category to the extent where it won’t really recover. I would imagine that the V8s will find it more difficult now to get sponsorship because sponsors only ask about one event, and that is the Bathurst 1000. But, by the same token, you’d also have to say that was their (V8 competitors’) call. They chose to go down that route (setting up their own race), and, in my opinion, it was a very dangerous and very brave route to go down.”

Gow later noted that interest from international entrants was “better than imagined,” with the event able to pick and choose which imports would be offered travel assistance.

Tony Cochrane from the V8 Supercars side of the argument subsequently returned serve, with vigour, the following week in AA:

“We have a record field going to both Melbourne (AGP) and Indy (Surfers Paradise), which makes a laughingstock of Alan Gow’s comments that we’ve got so many teams that want to jump ship supposedly to his Two-Litre thing. It’s sad really. I feel sorry for the man – he’s obviously a pathetic little man if that’s the best he can come out with. We certainly believe that we’re not only going to survive, but very much prosper with the renewed television time and the renewed interest from key sponsors and the fabulous drivers and teams which are already a part of the scene. It’s just ludicrous to say that we’re the ones struggling. Just compare our audience last year with their audience. Just compare our TV times this year – compared with their TV times, none of which are live. Compare the size of their grids with our grids… here is a group which couldn’t raise a sufficient grid to run at Indy and who are only running in Melbourne because they are propped up by another category. And yet we’ve been accused of being the ones on the way out – it’s frightfully pathetic. I think they’ll find if they spend as much time looking after their category as they do firing cheap pathetic shots at us it will do them better.”

The ship jumping alluded to by Cochrane ultimately was a one-way street in Supercars’ direction, with the likes of Brad Jones Racing, Paul Morris Motorsport, Greenfield Mowers Racing, Aaron McGill Motorsport, and John Henderson all fielding V8s.

Adding to the intriguing mix of power plays, the ARDC launched its V8 Challenge for privateer-run V8 Supercars. The calendar focused on Amaroo Park and Eastern Creek, and it grew to include a place on the first Bathurst undercard.

In essence, it was a revival of the AMSCAR series that petered out in 1993.

CAMS, however, stated that it would not sanction the series for various reasons, nor allow it to take place on the October long weekend schedule.

One of the significant stumbling blocks for the start-up was the fact that TEGA owned the only CAMS-approved engine monitors for the cars—the ARDC would have to acquire these or develop a system of its own. Scheduling clashes with V8 Supercars events were also an issue.

Cochrane chimed in to AA:

“What I find strange is this group (ARDC and the Mount Panorama Consortium) were saying, not long ago, that V8s didn’t have a future and eventually they’d have to change to Two-Litre. Now, when it’s clear V8 Supercars are the stronger, have got the fan base and the TV audience, they want to revisit V8s and have a major V8 race during their program! Would they please make up their mind. Let them get on with Two-Litre racing, we’ll get on with V8 racing and let the fans choose.”

The grumblings of legal action would linger, with the class eventually rebranding itself as AMSCAR, for which a four-round series was contested, with fields of 15 ground down to eight starters by the December finale.

Mal Rose was crowned the series champion from Mick Donaher and Allan McCarthy. The trio split all of the race wins, even though the latter pair skipped rounds.

It was the end of the line for a series that provided a generation of Sunday afternoon thrills on Channel Seven from Amaroo Park.

Elsewhere, and as noted by Cochrane, above, the Super Tourers were dropped from the IMG-promoted Indycar race, with multiple reasons noted, including TOCA not being able to guarantee grid sizes and a lack of corporate sales, with the series’ one corporate facility from 1996 outdone by $80,000 worth of sales to the HQ Holdens alone.

TOCA bit back, citing IMG and Cochrane’s involvement in both the Indy meet and AVESCO as a clear conflict.

At the same time that Super Touring signed on for the first weekend in October, the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix at Phillip Island was confirmed to run head-to-head on the same date.

It was unfortunate timing for Australian motorsport, with the call coming from an international desire for the bike race not to clash with the Japanese F1 GP.

The end result of the rescheduling was that Channel Ten’s motorsport programming competed with Seven’s telecast from Bathurst.

Elsewhere, both tin-top categories put their hats into the ring for an invitation to New Zealand at the end of the season. AVESCO noted that circuit safety would have to be brought up to scratch before any deal was done, following an at times messy toe-in-the-water exercise at the end of the 1996 season with a field of 12 cars.

By the end of March, GT-Production were a scratching from the Super Tourer 1000; instead, the category would have a standalone three-hour race on the Saturday afternoon of the Australian 1000 Classic as a curtain-raiser to the V8 Supercars race.

It was a big move—the Ross Palmer-owned category was a mainstay of the Super Touring Championship undercard and remained that way until the start of the 1999 season.

PROCAR noted that the V8 Supercars offer was the only serious one on the table, and it ensured a strong TV package for competitors.

The Mount Panorama Consortium countered that the worldwide interest from Super Touring quarters meant that the production cars were not required to bolster the field.

At AVESCO in April, Wayne Cattach was appointed Chairman following the resignation of BMW stalwart Ron Meatchem.

In June, TOCA Australia CEO Kelvin O’Reilly admitted to writing to AVESCO, IMG, Network Ten and TEGA, threatening to sue under the Trade Practices Act if they failed to change the name of the Australian 1000 Classic and if they didn’t move their event to a date ten weeks away from the first weekend in October.

In the same Auto Action article, O’Reilly defended claims that less than 400 spectators attended the Phillip Island Super Touring round: “Even not counting the corporates, we had many more than 350 paying spectators… we don’t give away free passes to the spectator areas.”

Following the opening handful of V8 Supercar rounds, Channel Ten pointed to the early ratings success of its coverage, especially along the eastern seaboard. However, the broadcast from the upcoming Perth round would be delayed a week due to the time zone difference.

Elsewhere, entries opened for the Australian 1000 Classic, with a $750,000 prize pool confirmed, with appearance money, tyre subsidies for privateers, and a reduced entry fee – down from the 1996 figure of $2,500 to $1,500, which was fully refundable to TEGA members.

To mark the occasion, TEGA joining fees were reduced from $3,500 to $1,500.

Assembling the Troops

It had to happen one day, but prior to the Lakeside round of the V8 Supercars Championship in June, Peter Brock dropped a bombshell on the sport by announcing his retirement.

Subsequently, record crowds came out of the woodworks on his Australia-wide retirement tour to see one last glimpse of the King of the Mountain in action.

Behind the scenes, and after much toing and froing, Brock was given approval from both Mobil and Holden to contest the Super Touring event. All signs pointed to a drive with the Triple 8 Vauxhall squad, which would receive a level of support from the local Holden factory.

The deal to see Brock race in the Super Tourer event was seemingly sweetened by an agreement with Channel Seven, for whom the nine-time champion hosted the ‘Police, Camera, Action’ program, with the consideration from the station rumoured to be in the vicinity of $250,000.

While some were of the belief that V8 Supercars drivers were banned from running in the rival event, who could possibly shut Brock down, and what could the possible sanctions have been?

He was the King, and this was his retirement party, where he had the opportunity to double dip for a tenth Bathurst win.

Brock positioned himself as a diplomat who could possibly bring the warring parties together.

The press was filled with speculation during the period, envisioning a world where slowed V8s could race on a level playing field with their Two-Litre counterparts, a concept that didn’t sit well with either party.

Meanwhile, at the start of July, Mount Panorama Consortium chief Greg Eaton noted that the Super Tourers were well on track to assemble a field of at least 40 cars, even if some squads were tardy filling out their paperwork.

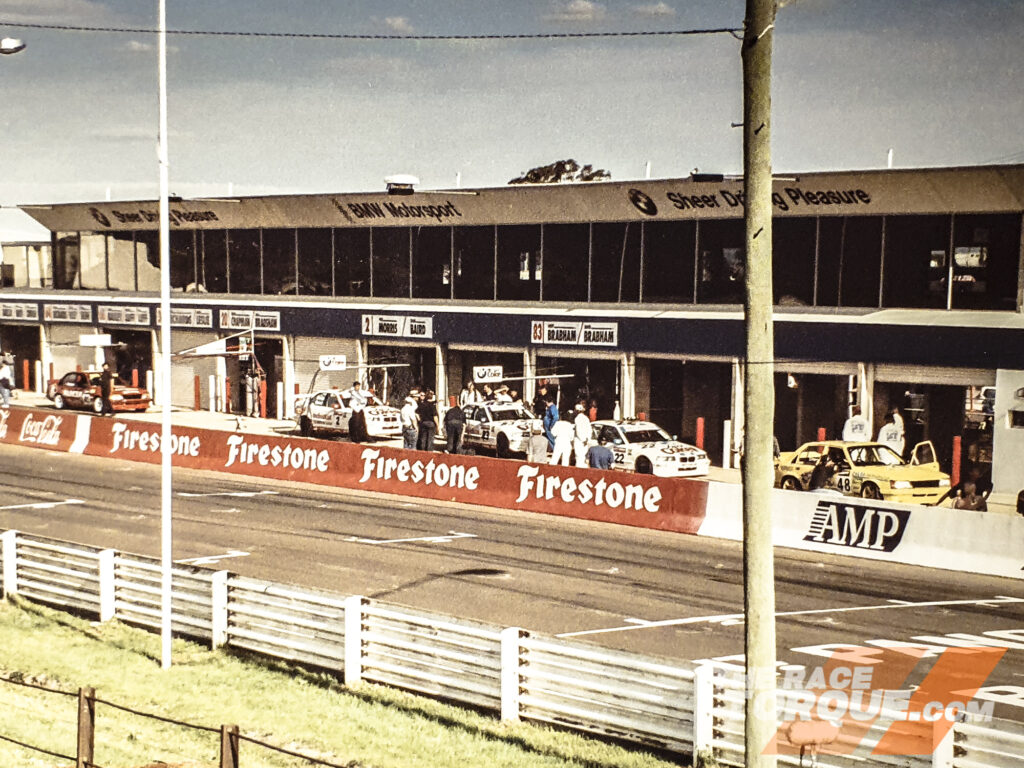

The Super Tourers took to Mount Panorama on Tuesday, July 22nd, for the pre-event media day. Craig Baird was on top of the pops, while the international broadcast package, which would cover Europe, Asia, the USA, and New Zealand, was confirmed.

Around this time, Cochrane, now departed from IMG and installed as Chairman of V8 Supercars, noted that the category wasn’t tethered to Bathurst in October. The 1998 date would move to either September, November, or Easter, following Indycar’s Gold Coast date switch to mid-October.

A couple of weeks after the August entry cut-off for the Super Tourer event, Nissan Motorsport Europe confirmed that their pair of entries would be non-starters following ongoing politicking in the BTCC after an early technical infringement by the squad.

The event revised its expected entry figure to 32, and what was described as a “quality field rather than a quantity field.”

Super Touring powerbroker Peter Adderton was proud to announce Russell Ingall alongside John Cleland in the second Vectra, following Brock’s lead to run both races.

V8 Supercars had the stars, a point it was eager to defend.

Ingall’s Bathurst Super Touring debut, however, would have to wait 12 months after reported contractual issues surfaced.

Earlier, Ingall’s team boss, Larry Perkins, never signed the contract he was offered for the same Vectra drive, after he used the exercise as a fact-finding mission.

James Kaye would eventually join John Cleland in the car, with Brock confirmed alongside Derek Warwick in an Australian Grand Prix-backed machine.

It was Warwick’s team, and he wanted to drive with Brock, even if it meant that PB’s old mate Cleland was shunted to the second car.

Come race weekend, Warwick, the faster of the pair, further showed who’s the boss in the top-ten shootout when Brock sat on the sidelines for the first time in his career while his car hit the track on Saturday.

A coup for the event came in the form of two Renault Lagunas from the BTCC-winning Williams squad, with F1 champion Alan Jones to reacquaint himself in the team alongside Graham Moore, with the lead car piloted by Alain Menu and Jason Plato.

The move would see another V8 star on the Two-Litre grid – but once again, how could anyone say no to Jones?

Elsewhere, a privateer Honda Accord from the UK was noted as an entry; however, that car never made the plane.

On the local front, Cameron McLean and Steven Richards’ regular steeds would remain parked up, while Justin Matthews/Bob Holden/Paul Nelson would be starters in their BMW, while third cars from BMW and Audi were mooted.

Richards, however, did make the show after Garry Rodgers said it definitely would not on multiple occasions, with Nissan in Europe coming to the party late with parts necessary to run the car.

One interesting combination floated was Gabrielle Tarquini and Neil Crompton in a Steve Horne-owned Honda out of North America.

The effort would fail to eventuate, but Crompton would wind up with a seat at Peugeot alongside Patrick Watts as a part of a two-car effort with Paul Radisich and Tim Harvey in the second entry.

Paul Pickett, meanwhile, entered his two Hyundais, with drives in the second car advertised for $20,000 a pop, as Hartong Motorsport confirmed its BMW from the USA, although a lack of budget would ultimately scupper that project, ditto another privateer North American entry.

If external pressure from upstairs in the V8 Supercars and Super Touring HQs dictated the driver market, some of the moves were fascinating come confusing.

Cam McConville, who was enlisted as a co-driver at Dick Johnson Racing for Bathurst Two, was a late withdrawal from that drive, preferring to concentrate on his Audi duties.

His replacement at DJR was none other than Craig Baird, BMW’s hired Super Touring factory ace…

While drivers like Brad Jones and Paul Morris skipped the V8 event, Steven and Jim Richards would pair together for Garry Rogers Motorsport, in what was a successful combination.

The entire list of Super Touring ins, outs and maybes was extensive – a wide array of teams and drivers were speculated to enter. However, many failed to become a reality come October, and the field was filled with local privateer entries.

At the time, air freight for the planned international visitors was expected to be in the order of $1 million, with Channel Seven rumoured to be selling sponsorship packages for some of the visiting entries.

On Tuesday, August 5th, V8 Supercars held its media day in Bathurst in front of an estimated audience of 10,000 spectators. Primus Telecommunications became the event’s title sponsor in a four-year deal that ultimately lasted one.

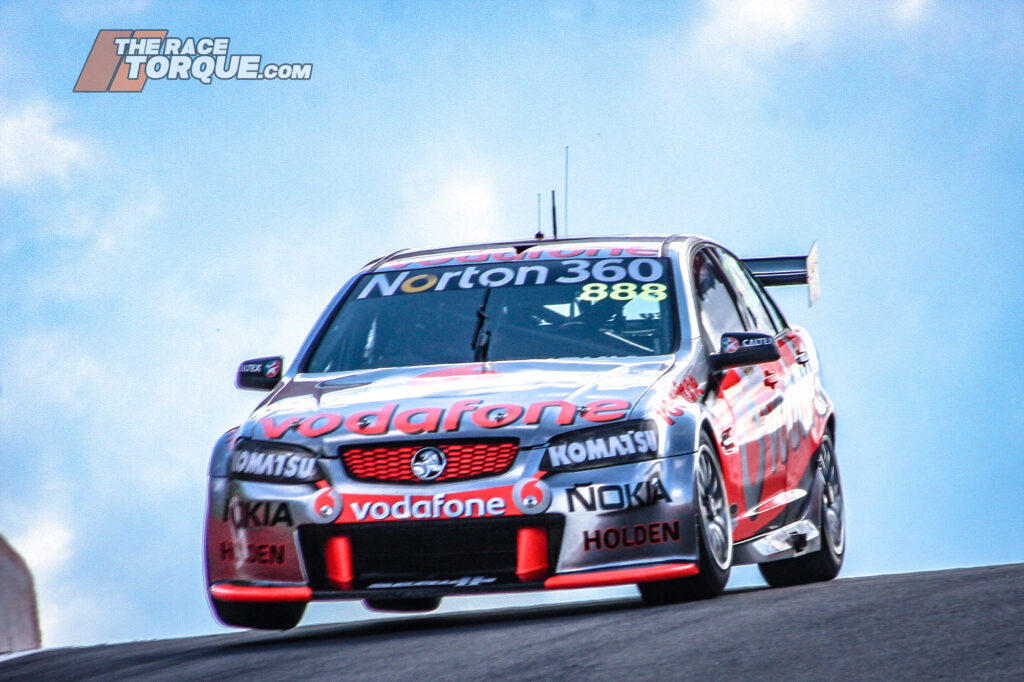

While Glenn Seton headed the top-ten shootout, there was plenty of drama elsewhere, with John Faulkner suffering a massive head-on impact at McPhillamy Park, Greg Crick survived a blown tyre through the kink at the Chase, and Larry Perkins wrote off his Commodore in the Esses with a head-on crunch into the wall after missing a gear at Skyline, as evidence in the above image from the Super Touring event.

However, with a new car coming on stream, it wasn’t a massive drama for the Castrol crew.

Meanwhile, it was noted that the ARDC-run AMSCAR curtain-raiser for the Super Touring race would carry a prize pool of $70,000; however, the class never made the final program.

By September, the third entries from BMW and Audi were withdrawn, Julian Bailey was enlisted alongside Warren Luff in a local Honda, while Matt Neal was confirmed with Steven Richards in the GRM Nissan.

On the TV front, Channel Seven confirmed live Saturday coverage from 2pm to 5pm and Sunday coverage from 8 am to 5pm, with the commentary team led by Murray Walker, Allan Moffat, and Garry Wilkinson.

V8 Financial Trades

In V8-land, moves were afoot to replace IMG’s marketing role in the sport by Sports and Entertainment Limited, while further work was ongoing to solidify the category’s franchise system with competitors.

Ultimately, SEL, formed by Cochrane, James Erskine, Basil Scaffidi, and David Coe in July 1997, would own a 25 per cent stake in AVESCO, with TEGA owning the remainder after the CAMS-owned AMSC finally departed the business.

While the conflict of interest with CAMS owning a small slice of AVESCO was an annoyance for some in the motorsport industry, so too was the potential lost income, an issue that continues to grind the gears of many within the CAMS hierarchy.

The disintegration of the relationship between AVESCO and CAMS was mired in uncomfortable and convoluted legal action that essentially worked to keep lawyers rich.

The issues seemingly stemmed from the casual suggestion by AMSC Chairman Byram Johnston, the nominal CAMS representative on the AVESCO board, that on legal advice, AVESCO did not own the rights to the V8 category in perpetuity.

Once everyone lawyered up, CAMS wasn’t really in a position to fight, but it soldiered on regardless.

The sale of the 10 per cent share was initially negotiated to carry a price of $4.8 million, but when someone on the CAMS side forgot to cancel a court case, that deal was off.

Ultimately, CAMS had to pay both parties’ costs, and the stake eventually sold for $4 million, which, in isolation, was a neat return after zero initial outlay.

AVESCO kept its rights unconditionally and in perpetuity while subsequently paying an annual $300,000 fee to CAMS for the provision of stewards and a judicial system.

Wayne Cattach described it as “The worst commercial deal in the history of motorsport anywhere.”

Elsewhere, the CAMS Official History noted that “CAMS sued, but the action ended in farce when it’s alleged CAMS’ lawyers missed the hearing.”

Years later, Cochrane revealed that the IMG share of the business cost SEL only $52,000, covering their expenses related to AVESCO at that point in time. Meanwhile, IMG retained management rights at Bathurst until the 2004 race, which, for them, was the crown jewel.

When SEL sold out in 2011 to Archer Capital, the sport as a whole was valued at $330 million, making the CAMS share at $4 million look like a certified bargain and SEL’s investment one of the best ever.

Archer looked to sell out its 60 per cent stake in 2017 to no avail before finally selling the portion to the RACE consortium in 2021 for a reported $57 million, with RACE also scooping up the team-owned share for another $35 million.

SEL bailed at the top of the game.

While it entered the sport with an annual championship TV audience of around 6 million, by 2010, the series had a cumulative season audience of 10.3 million, an average Sunday race viewership of 750,000, 1.71 million Bathurst viewers, and an average attendance of 126,000 at its 14 rounds.

Next up in part three: When the racing starts, the bullshit stops, albeit temporarily: twin race weeks on The Mountain with the AMP Bathurst 1000 and the Primus Australian 1000 Classic.